Vaccine history tells how immunization developed—from early, risky attempts at disease prevention to today’s carefully designed vaccines. This journey began in earnest with the smallpox vaccine, which used cowpox material to protect against smallpox. Over centuries, clinical insights, laboratory breakthroughs, and public health campaigns combined to turn once-deadly infections into diseases we can now prevent.

What are vaccines and where does the story begin?

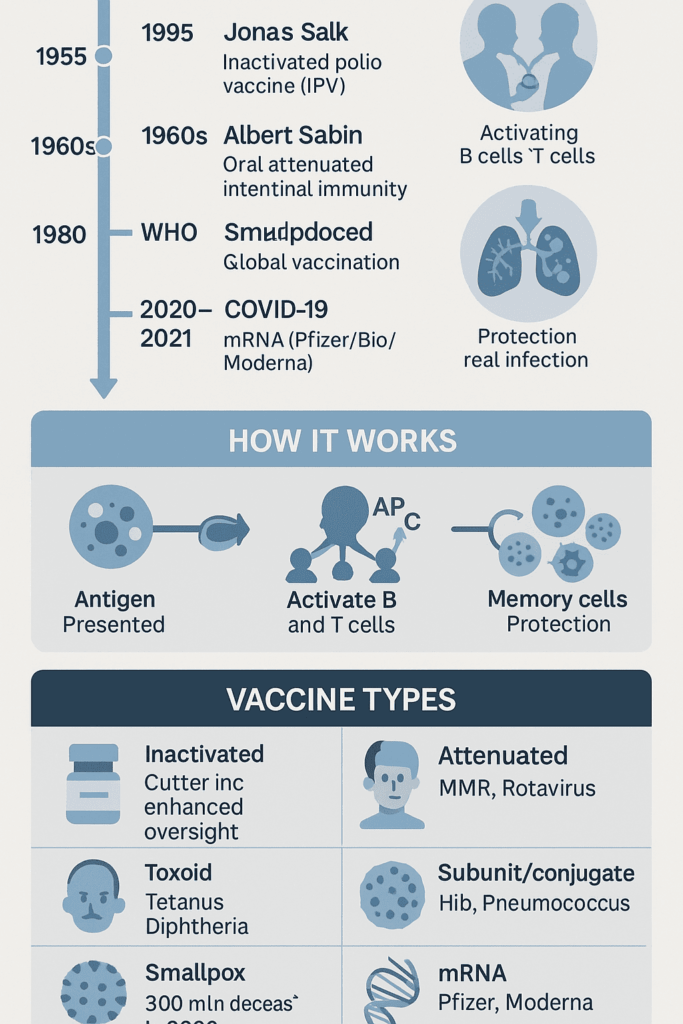

Vaccines are biological tools that safely introduce the immune system to a pathogen’s key features. They use inactivated organisms, weakened strains, purified protein pieces, toxoids, viral vectors, or even genetic material like mRNA. The goal is to build immunological memory—so when the real threat appears, the immune system can respond quickly and prevent serious illness.

Long before scientists explained how vaccines work, communities facing smallpox—a highly contagious and deadly disease—turned to variolation. This practice involved introducing material from smallpox sores into a skin cut, hoping to cause a mild infection that would protect against future outbreaks. Variolation emerged independently in Asia and Africa, later spreading to Europe and North America. Its use sparked heated debates about safety and ethics among doctors, clergy, and the public. In 1721 Boston, Cotton Mather advocated for smallpox inoculation during an epidemic. He faced such fierce opposition that someone even threw a bomb into his home (Source: wvu.edu, 2025). Variolation relied on actual smallpox material, so while it could prevent future disease, it also carried real risks—including severe infection and the chance to spread the virus to others.

The real breakthrough came with Edward Jenner, an English physician who noticed that milkmaids who caught cowpox rarely developed smallpox. In 1796, Jenner tested his theory by inoculating a young boy with cowpox and later exposing him to smallpox. The boy did not get sick. In 1796, Jenner famously vaccinated James Phipps using cowpox from Sarah Nelmes, proving protection against smallpox and establishing the practice of vaccination (Source: cdc.gov, 2024). Jenner’s vaccine was much safer than variolation since it didn’t use smallpox itself, greatly reducing risk for recipients and those around them. The term “vaccination” comes from “vacca,” Latin for cow, honoring cowpox’s role.

Jenner’s success opened the door to a new era in vaccine science. Louis Pasteur, a French scientist, later connected germs to disease and developed the first lab-created, intentionally weakened vaccines. His work led to the first vaccines for veterinary anthrax and, most notably, rabies. Pasteur showed that immunity could be trained without causing the actual disease.

The evolution from variolation to Jenner’s cowpox vaccination and later to Pasteur’s laboratory-attenuated vaccines marks the conceptual progression from empirical inoculation to scientific immunoprophylaxis.Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2005

Pasteur’s development of attenuated vaccines, culminating in the rabies vaccination in 1885, established laboratory control over immunogens and inaugurated modern vaccine science.Plotkin SA. Vaccines: past, present and future. Nat Med. 2005

Milestones and makers: a timeline from smallpox to COVID-19

The innovations sparked by Jenner and Pasteur transformed global health. The campaign to eradicate smallpox, declared successful by the World Health Organization in 1980, stands as a landmark achievement. By pairing a safe, effective vaccine with targeted vaccination, surveillance, and ring containment, smallpox became the first human infectious disease ever eliminated worldwide.

Global smallpox eradication, certified in 1980, followed strategic deployment of potent vaccinia-based vaccines with rigorous surveillance and containment.Fenner F et al. Smallpox and its Eradication. WHO, 1988

The mid-20th century brought more progress. Jonas Salk, an American virologist, introduced the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) in 1955. His vaccine used killed poliovirus to trigger immunity without the risk of causing polio. Albert Sabin later developed an oral, live-attenuated polio vaccine, which provided strong gut immunity and helped stop virus transmission in communities. Today, both IPV and oral vaccines are used to balance safety and effectiveness in the fight against polio.

The tandem development of IPV (Salk) and OPV (Sabin) provided complementary tools—parenteral inactivated vaccine for safe, durable humoral immunity and oral attenuated vaccine for mucosal immunity and transmission control.Nathanson N, Kew OM. From emergence to eradication: the epidemiology of poliomyelitis. Prog Med Virol. 2010

During the later 20th century, vaccines expanded to cover diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, Haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B, pneumococcus, rotavirus, human papillomavirus (HPV), and seasonal influenza. Each new vaccine built on Jenner’s original principle: safely priming the immune system before exposure.

Who developed the COVID-19 vaccine? The answer is many teams. Decades of immunology research enabled the first authorized COVID-2 vaccines. The first mRNA vaccines—BNT162b2 (BioNTech and Pfizer) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna and the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)—set the pace. Soon after, vaccines using viral vectors and protein subunits followed: ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford/AstraZeneca), Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson), NVX‑CoV2373 (Novavax), Sputnik V (Gamaleya), BBIBP‑CorV (Sinopharm), CoronaVac (Sinovac), and BBV152/Covaxin (Bharat Biotech). A key advance was nucleoside modification, which helped mRNA vaccines work safely and efficiently at pandemic speed.

Nucleoside-modified mRNA reduces innate immune sensing and improves translation, providing a practical path for mRNA vaccines.Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2005

Randomized trials demonstrated safety and high efficacy for the first authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273, during the initial pandemic waves.Polack FP et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020; Baden LR et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021

Vector and protein-based COVID-19 vaccines broadened global options, with supportive efficacy and effectiveness data across multiple platforms and settings.Voysey M et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. Lancet. 2021; Heath PT et al. Safety and Efficacy of NVX‑CoV2373. N Engl J Med. 2021

From Jenner’s cowpox experiment to Pasteur’s lab discoveries, through Salk and Sabin’s polio breakthroughs and the rapid creation of COVID‑19 vaccines, the thread is clear: the steady refinement of how we present antigens to the human immune system. Connections among these milestones—variolation, smallpox vaccination, Pasteur’s rabies vaccine, and smallpox eradication—form a scientific story that still shapes how we design, test, and deliver new vaccines.

Public health impact: what changed and how do we measure it?

To measure vaccine impact, public health experts compare disease rates, deaths, and disabilities before and after vaccines are introduced. They also examine how quickly outbreaks are controlled and how stable the results remain. The most dramatic example is smallpox, which once caused high death rates and scarring. Thanks to the smallpox vaccine, the world moved from regular epidemics to complete eradication. This vaccine directly targeted the smallpox virus, making global elimination possible through ring vaccination and close surveillance. About 300 million people died from smallpox in the 20th century before eradication (Source: ourworldindata.org, 2024).

Polio shows a similar story. Once, polio outbreaks led to widespread paralysis and death. Now, thanks to both inactivated and oral vaccines, cases are rare. In countries with strong health systems, rising vaccine coverage made stopping transmission possible. Global strategies now focus on finishing eradication and managing the remaining risks.

Inactivated poliovirus vaccines (IPV) have been central to the global reduction of poliomyelitis and remain critical to the endgame and post-eradication risk management.Source: Advances and challenges in poliomyelitis vaccines: a comprehensive review of development – Liang J, Zhang Q et al. (2025) https: //europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC12307498

Measles demonstrates how vaccine design and program planning work together to change disease patterns. The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) shot, protects most people after one dose and nearly everyone after two. Since measles spreads easily, programs aim for two-dose coverage of at least 95%. Where countries achieved this—using both routine schedules and catch-up campaigns—measles cases dropped quickly, hospitals emptied, and deaths fell. In Africa, regular vaccination drives and a second routine dose have sharply reduced measles, though outbreaks still occur where coverage slips. These improvements aren’t just due to better detection; they reflect real declines in illness and complications.

Vaccines do more than prevent childhood diseases. For example, oral cholera vaccines now help control outbreaks in areas with unsafe water. In African regions where cholera threatens vulnerable communities, emergency vaccination campaigns work alongside water and sanitation projects, shrinking outbreaks while infrastructure improves.

In developed countries, vaccination rates climbed from moderate childhood coverage in the late 20th century to consistently high levels in the early 21st century. By the 2000s, most high-income nations reached over 90% coverage for multi-dose series like diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis. The COVID-19 pandemic caused some temporary drops in routine vaccinations, but catch-up efforts and school checks have restored much of the lost ground. Adult vaccination has also grown, expanding from mainly flu shots to include tetanus, pertussis, pneumococcal, and shingles vaccines, often through pharmacies and workplaces. The overall pattern is high coverage, with occasional challenges that require outreach and easier access.

The introduction of the HPV vaccine changed cancer prevention. By targeting the virus types that cause most cervical and other cancers, routine vaccination of adolescents has led to sharp drops in precancerous lesions and early signs of falling cancer rates. High uptake among both girls and boys, combined with screening, shifts HPV-related disease from late detection to prevention—a crucial advance, especially where screening is limited and cervical cancer deaths are high.

From shot to immunity: practice, schedules, and lifelong protection

Understanding how vaccination leads to immunity is key. Vaccination means giving a vaccine—a preparation that safely introduces antigens from a germ or toxin. Immunization is the process of becoming protected. This can happen actively (through vaccination or infection) or passively (by receiving antibodies from another person, such as a mother or a medical treatment). In short, all vaccination aims for immunization, but not all immunization comes from vaccination.

Which vaccines last a lifetime? Some, like the measles and rubella vaccines, give long-lasting, often lifelong protection after the full series. A single yellow fever shot is usually enough for life. Hepatitis A and B vaccines seem to protect for decades, likely for life in healthy people, even if antibody levels fall over time. Others, such as tetanus and diphtheria, need regular boosters because the body’s antibody levels can drop below protective thresholds.

Diphtheria, a serious bacterial infection, is prevented by a toxoid vaccine that trains the immune system to neutralize the toxin. Tetanus, caused by a neurotoxin, requires a toxoid vaccine and boosters every 10 years to maintain protection; adults should get at least one dose containing pertussis (Tdap). Hepatitis A and B vaccines use inactivated or recombinant viral components. Most healthy people don’t need hepatitis boosters after the initial series, though some high-risk or immunocompromised individuals may need extra doses or testing.

Maintaining high vaccine coverage remains important, even for diseases close to eradication. After polio was nearly eliminated in many countries with IPV schedules, keeping up routine immunization protects communities from imported cases and vaccine-derived strains, especially where coverage is uneven.

Keeping up with vaccinations, like the polio vaccine, is crucial for preventing the return of serious diseases in communities. This study from Italy underscores preparedness for poliovirus and diphtheria reintroduction when coverage falls.Source: Preparedness and response to the international poliovirus and diphtheria reintroduction – Milani M, Nicoletti M et al. (2025) https: //europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC12176779

Are vaccination records public? No—they are personal health records, protected by privacy laws in most countries. Public health agencies may share summary statistics, but access to individual records requires permission or a legal reason.

How do you find your old vaccination records? Start with your current and former doctors; pediatricians and primary care offices often keep immunization histories and may offer them through online portals. Schools, universities, and employers that required proof of vaccination may have records. Pharmacies and travel clinics can provide documentation for vaccines they administered. Many countries and U.S. states have Immunization Information Systems (IIS) that store lifetime records; you can request your record directly or through your provider. If you’ve traveled internationally, check for an International Certificate of Vaccination (“yellow card”). If records can’t be found, doctors may order blood tests or recommend re-vaccination—extra doses of most routine vaccines are safe if documentation is missing.

This paper reviews the progress and challenges in polio vaccination, showing that inactivated polio vaccines (IPV) have played a key role in reducing disease and will remain important for long-term protection strategies.Source: Advances and challenges in poliomyelitis vaccines: a comprehensive review of dev – Liang J, Zhang Q et al. (2025) https: //europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC12307498

Trust, movements, and public perception: from polio to the present

Public trust in vaccines is shaped by experience, advocacy, and dissent. In the early 18th century, networks in cities and colonies spread medical ideas as much as doctors did. Cotton Mather, a Boston minister, promoted variolation during the 1721 smallpox epidemic after learning about it from Onesimus, an enslaved man who described African variolation. In Boston, the adoption of variolation sparked controversy—sermons, pamphlets, and town hall debates fueled both support and resistance. This episode shows that vaccine acceptance and hesitancy are as much about social dynamics as science. Relationships—like the one between Onesimus and Mather—shaped how new practices spread.

Throughout the 19th century, labor groups, religious communities, and civil libertarians challenged compulsory smallpox vaccination, while health officials and civic groups promoted it as a duty. These debates led to changes in laws, safety improvements, and better communication, laying the groundwork for today’s idea that vaccination needs both scientific rigor and community trust.

The polio vaccine changed public attitudes on a large scale. The March of Dimes campaign used radio, schools, and neighborhood events to personalize the fight against polio and fund research. When the Salk IPV was declared effective in 1955, celebrations broke out, school clinics opened, and the media reframed vaccination as a hopeful act. Parents who remembered polio outbreaks and iron lungs saw the vaccine as real protection. However, a manufacturing error led to cases of vaccine-associated polio, reminding everyone that trust depends on safety and transparency.

Once those problems were fixed, mass immunization days with the oral Sabin vaccine in the 1960s reignited community involvement. Local clinics, faith groups, and schools made vaccination a shared experience. In recent decades, hesitancy has resurfaced—driven by misinformation, historical injustices, polarized media, and parents’ questions. Supportive movements—patient advocates, survivor networks, professional groups, and community leaders—have countered by sharing real stories and clear evidence. Uptake improves most when efforts respect local values and address barriers like access, convenience, and cost.

Vaccine hesitancy arises from contextual, individual, and vaccine-specific factors—trust in institutions, perceived risks, and communication quality—and directly affects uptake and community protection; durable solutions require transparency and genuine community partnership.Source: Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. – Nuwarda RF, Ramzan I et al. (2022) https: //europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC9612044

Safety, regulation, and lessons learned

The Cutter Incident—a 1955 failure in IPV manufacturing that caused polio cases—marked a turning point for vaccine oversight. Because IPV depends on complete inactivation, any lapse can let live virus slip through, as happened in some early batches, leading to paralytic disease. The 1955 Cutter Incident caused over 250 polio cases, forcing a pause and stricter controls. The U.S. switched to OPV for routine use in 1962, a practice that lasted until 2000 (Sources: cdc.gov, 2024; chop.edu, 2025). This shift reflected both the need for safer mass campaigns and the effort to rebuild trust while IPV manufacturing improved.

Regulators responded by tightening every step: more lot testing, better inactivation and potency checks, strict process validation, and thorough facility inspections. They also improved cold-chain monitoring and adverse event reporting. The lesson wasn’t just to add more tests, but to build redundancy and transparency into the whole system—so every checkpoint, from formulation to shipping, helps catch rare but serious errors.

Another lesson: when safety issues arise, clear explanations about what happened and what changed help maintain public trust. Over time, this approach restored confidence in IPV, now the backbone of polio control in many countries, while OPV remains crucial for stopping outbreaks in certain regions. The lasting legacy is a safety culture that treats community trust as the most precious ingredient—earned through quality, vigilance, and open communication.

What’s next: new platforms, global goals, and preparedness

The rapid development and rollout of COVID-19 vaccines reshaped what immunization programs can achieve. It also revealed areas that need strengthening before the next emergency. Recognizing these pressure points is vital for future pandemic readiness.

What challenges did the COVID-19 vaccine rollout face? The hurdles were interconnected: scientific, manufacturing, logistical, regulatory, and social. Global supply was limited by the speed of technology transfer and shortages of key materials, like specialty lipids for mRNA vaccines. Production also hit bottlenecks for fill-finish capacity, vials, stoppers, and special syringes. Export controls and competition between countries delayed access for many low- and middle-income nations, even with initiatives like COVAX. The need for ultra-cold storage for early mRNA vaccines added complexity—requiring freezers at −70 °C, validated transport, and careful handling after thawing. Programs also had to track two-dose schedules, adapt to changing booster guidance as new variants spread, and manage evolving data requirements. Safety monitoring needed to catch and communicate rare side effects—like myocarditis after mRNA shots or blood clots after some vector vaccines—while keeping risks in perspective. Staffing, mobile clinics, and outreach for vulnerable groups stretched public health systems. Digital appointment systems helped some, but created barriers where internet or tech skills were limited. Finally, widespread misinformation made clear, trusted communication more important than ever.

- Supply chain and manufacturing: technology transfer, raw materials, fill-finish, and export restrictions.

- Cold chain and last-mile logistics: ultra-cold storage, validated transport, and managing multi-dose vials to reduce waste.

- Program design: two-dose coordination, adapting to new variants, and workforce coverage for clinics.

- Regulatory and legal: emergency use listings, reliance pathways, safety monitoring, and injury compensation systems.

- Safety monitoring: transparent reporting of rare adverse events with balanced risk messages.

- Equity and access: early allocation gaps, COVAX limitations, reaching hard-to-reach groups, and disability-inclusive services.

- Data systems: secure, interoperable registries that don’t exclude people without digital access.

- Community engagement: countering misinformation, supporting informed consent, and working with trusted local leaders.

Good coordination and teamwork among different groups can make large health efforts more successful. For weight loss, having support from family, friends, and healthcare providers helps people stick with the program—and the same principle applies to vaccine rollouts: strong collaboration improves outcomes.Source: The COVID-19 Vaccination Rollout in Tanzania: The Role of Coordination in Its Su – Rwegerera F, Mwenesi M et al. (2025) https: //europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC12116031

Countries that set up coordination groups—including health leaders, logistics experts, local governments, civil society, and private partners—were able to solve problems faster and match supply to demand more efficiently. When outreach relied on existing community networks—faith leaders, unions, neighborhood groups—vaccine uptake and completion improved.

Trust, clear information, and support from local leaders make it easier for people to take up new health programs. If you’re trying to lose weight, finding a supportive group helps; in vaccination, locally trusted messengers and tailored communication are similarly decisive.Source: Understanding factors influencing the implementation and uptake of less-establis – Ojumu A, Ibrahim SA et al. (2025) https: //europepmc.org/article/MED/40799014

Looking ahead, preparedness goes beyond scaling up manufacturing and cold chain. It also means designing products that are easier to deliver. Thermostable vaccines, single-dose schedules, nasal or oral vaccines, and microarray patches could all help reach more people with less effort. Self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA) may allow lower doses, while protein vaccines with adjuvants can offer durable immunity with standard refrigeration. Faster regulatory pathways and agreed safety protocols can speed up safe rollout. True equity will require contracts for technology transfer, regional manufacturing, and financing that ensures all regions—not just wealthy ones—get vaccines at the same time.

Preparedness also includes planning for deliberate biological threats. Anthrax, caused by Bacillus anthracis, is a classic concern due to its durability and potential for aerosol spread. Current anthrax vaccines protect at-risk workers and responders, but newer options—including recombinant and possibly mRNA-based vaccines—aim to simplify schedules and improve tolerability. The same production, cold-chain, and safety systems used in COVID-19 responses will be crucial for rapid vaccination after an anthrax event, linking biodefense to broader vaccine system strength.